A Time in Taiwan

The End 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

最後之章

Taiwan taught me nothing I couldn’t have learned elsewhere. But it did take a place so foreign. When I entered the Orient, it wasn’t as if some path to zen unravelled before my eyes. I didn’t come away with a distinct opinion of people I saw, nor a reformed one of those I left behind; my conceptions, if anything, are only more muddied than when I started.

But without the friends and customs and justs-because I had woven, for years, into my nest, I was free of all expectations; I enjoyed life anew. In the presence of the familiar I’d have ended up circling back to retain a worthless consistency of character.

If I wanted to be more genial, cynical, combative or gentle, reserved or not there were no inscriptions on my arm to haunt me for it. There is a certain rhythm of character to which you sync after hearing it for so long. That soundtrack wasn’t present in Taiwan. I was pleased to find nothing in my nature calcified.

I learned what is time well-spent and what is time wasted; for a while I’d debated whether the difference was real and if it would ever present itself to me. Each decision sprouts a plant in your life that is designless, and also incomparable. So how would you know?

But I’ve learned a better intuition of those things, and I can sum them up: be present. Always. From the simplest attention you pay to a creature, to your coffee conversation or just taking action as opposed to not, you will be rewarded tenfold. I caution especially those who begin to start the long decline into comfort decades before nature forces them to. If someone claims to make it worth your while to just sit tight, to just stick it out a little bit longer in a place you don’t want to be with a person you’re lukewarm about, run.

And be wary of those who are not present, and there are many of them; who won’t afford you the crumbs of their thoughtfulness, or will but only if paid in spades. Everyone has a price for the resource they hold most dear, that is, time. Make sure that those you care about barter it equally with you.

And one more thing. Take the experience. No matter how much you think you know from what others have told you, your circumstances are not the same. You know nothing, and will only know by doing. Everything non-factual that you learn from someone else is steeped in and strained through their persona. You can just throw that swill out. Learn it yourself.

Yes. If I’m going to be in this stream, and nothing and no-one is constant, then I will take the experience. Sure, I’ll enjoy a few turns in a whirlpool. And then I’m swimming on.

第二十章

Two days day before my flight, I stopped in Hualien City (花蓮市) for a beautiful weekend. I’d spent so many nights on the back of my friends’ scooters, inhaling the ambient tar of a thousand lit Kaohsiung men, without helmet and carving through choked alleyways to avoid the cops, but without worry, that to finally be in seaside Hualien was like plunging my lungs into the depths of a salt mine.

I borrowed a bike from the hostel and made for Carp Lake (鯉魚潭), stopping at one of the numerous FamilyMart (全家) convenience stores for a cheap two-liter water and a bag of cocoa-covered, sugar-dusted roasted hazelnuts. I took the bike trails along the stream and the air passing over it chilled the ride to comfort. I found nobody in the pastoral houses that bordered it.

I stopped and slept in the ample grasses surrounding Carp Lake, and through flagging eyes saw dogs basking for moments and then repositioning themselves as if playing meadow-musical chairs. It appeared to be a sanctuary for maimed dogs. A long, vigorous black one with a shiny coat cantered toward me like a three-legged egg beater; another, smaller white one, missing the paw of his front right leg, acted leery until I reminded him of the man-dog relationship and threw him a stick.

After thirty minutes I awoke to the all seven of the lake dogs converging on the low grumble of a hatchback on gravel. The five still blessed with tails wagged them furiously; those without mimed their gladness. An old Taiwanese couple got out, and cup-by-cup fed the hungry dogs, accepting the utmost adoration in return. I was jealous, but in their distraction I ate my cocoa nuts without the lust of a dog who doesn’t know what’s good for him, and headed home.

The next day, H’s daughter took a two-hour bus ride from her university in Taiwan’s capital to accompany me on my last day, in an extended hospitality I’d expect only from the Taiwanese. We resolved to meet at the small park in front of the station. When she told me, with eighty-percent emoticon saturation, that the bus would be late, I took a walk around and inhaled a few braised chicken thighs with rice for a plate lunch.

I rented a 100cc black Kawasaki with my water-warped, but virgin, international driver’s license. I told H’s daughter that I’d be driving. She didn’t hesitate to mount the back, having already internalized the tradeoff between father-approved foreign-driver and the hassle of driving herself. I began down the northwest spoke out of the city, topping out the tiny bike at 80 km/h. I could taste the breeze freshening minute by minute as the strip mall outskirts ceded to the mountains of Taroko Gorge National Park (太魯閣國家公園).

Taroko Gorge is like the Grand Canyon, but with roads cut by blood labor in the style of John Henry; hundreds of tunnelers’ skulls were flattened by boulders (and many of those intact just died of fatigue) for this crème of Taiwan. With H’s daughter aboard, I barrelled through the sinuate elevation and stopped from time to time for a hike to one of the many temples. H’s daughter would often catch her breath halfway, prodding me to continue alone, being fit only in the Taiwanese way of eating little and exercising similarly little. This allowed me solitarily claims on a view from or atop Buddhist sanctuaries nestled in a grove.

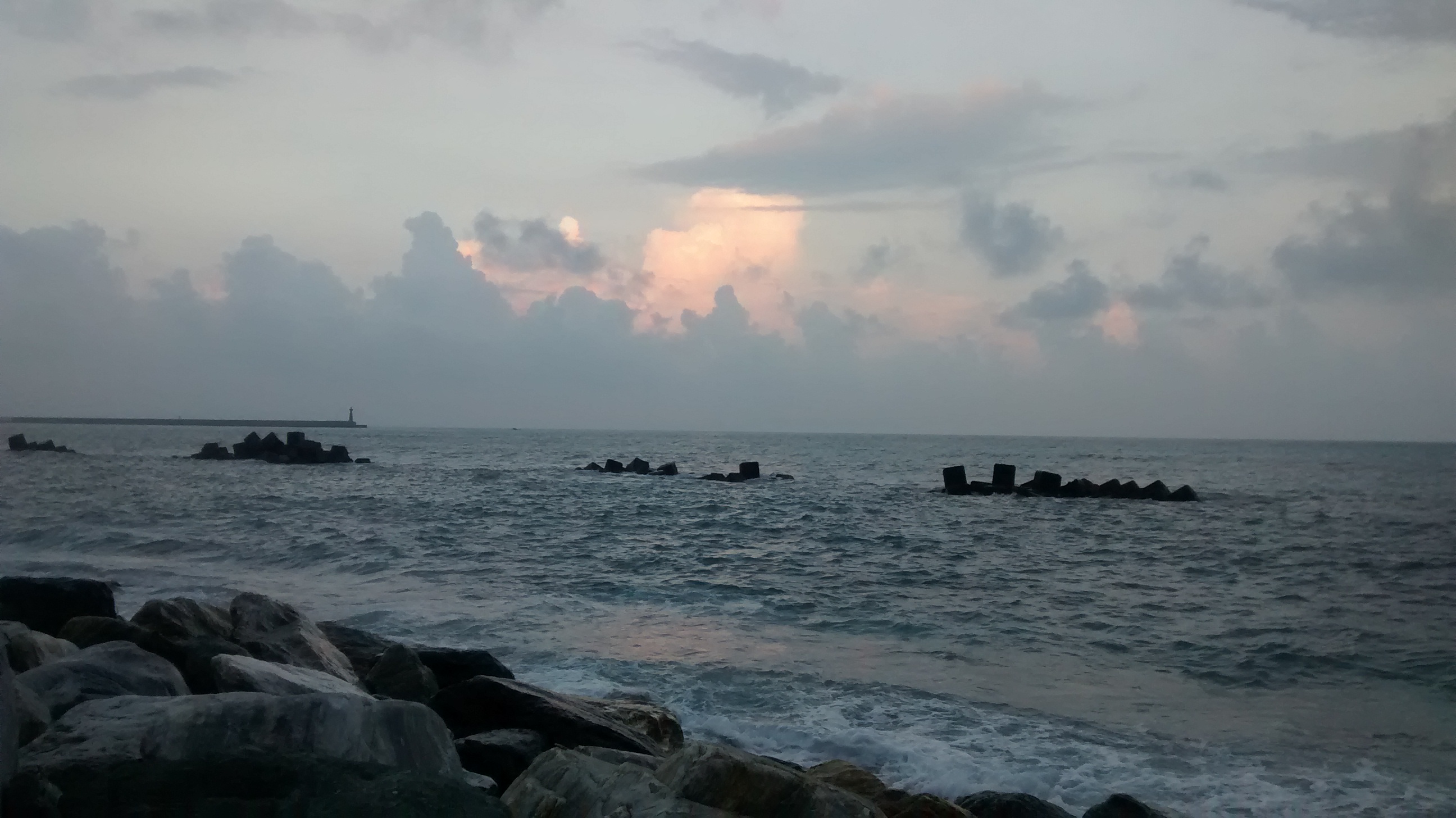

We left in the early evening to catch a sunset at North Ocean Park (北濱公園), and on the way H’s daughter fell asleep while upright on the back of the scooter. How this is possible or why one would dare I still don’t know; but I took it as a subtle compliment to my smooth riding. We stopped for tea and a mango shaved ice before heading out to the rocks. The cold, vortical Eastern shore beguiled not a single soul to enter. On the way home through the park, a man shared just what he thought of two dogs taking turns penetrating each other. 兩個都是功人,你知道嗎?真的變態!They’re both males, you know. How perverted!

He joked, but I could tell that if I chanced to disagree he’d blow the conservative magma that roiled within. The Taiwanese way is not live-and-let-live, and for that I was relieved to be on the way out. A beautiful country and a kind people, if you stay on the railroad tracks. H was an exception. He took care of me like his own son, a foreigner with no convential job and little to offer but another perspective, and for that I am grateful. I left, ambivalent, on the slow train out of Hualien.

第十九章

I’m making a counter-clockwise tour around the island, last stop: the airport. A few days ago I hung out with my Kaohsiung friends for the last time. One of them is a large Siberian man who looks confusingly East Asian – which, he’d tell me in his thick Russian accent, a full half of all Siberians look. And I’m not Mongolian. Seriously. Nothing against them. But I’m not. He invited me over, and we spent the afternoon in a haze, eating bags of the oatmeal cookies they sell at Metro station Red Line No. 15 (巨蛋), and the Russian chocolate his mom mails him by the kilo.

He grew whimsical and started shooting pellets out of the window at a government compound with his ersatz pistol, so I suggested we divert our terrorist excitement to frisbee in the park instead. Afterwards, he went back to sleep since he had a night shift and the rest of us enjoyed some tasty Taiwanese specialties, including brown-sugar shaved ice with grass jelly (黑糖仙草雪花冰), and fried Stinky tofu (炸臭豆腐).

The next day was my last meeting with H and his family. A few days earlier H and I had gone to Metropolitan Park (都會公園) in Kaohsiung and chatted for a few hours, where we talked about people’s life temperaments and platitudes about relationship compatibility; the chaff of old men’s rants. It was one of the few nights where it was clear enough to see stars. I consider low air pollution in Kaohsiung to be auspicious.

H showed me that he’d written notes of all of our meetings – the last was our twenty-fifth – in a small blue notebook. We’d first met through an online language-exchange forum, and like most online forms, I had purposely filled in deceptive details on questions I considered too invasive. The first page in his diary read like a slap in the face from reality. Ashwin is different age than he said. Ashwin is not actually married. Ashwin is not really from Burmuda [sic].

On our last day we went to the southernmost county of the island, Kenting (墾丁). H’s wife has a dream of opening a coffee shop one day (who doesn’t), and we stopped by the coast for some overpriced truck-made coffee, the likes of which I haven’t seen since I left the Bay area. She finally let me treat her, a poor return for the sheer amount of fresh-boiled pumpkin milk (南瓜牛奶) she has made for me at her house over the months.

Later, I descended an easy cliff, stripped down to my boxers and enjoyed the ocean. When I climbed back up, I was greeted by bewildered Taiwanese taking videos of me. H told me that in Taiwan, even at the beach, a bit more modesty is the norm. Wet, dong-hugging boxers do not count.

We were tired from swimming and walked around a night market as we’d done so many times before. He dropped me off at the railway station connecting the west and east halves of the island, Fangliao (枋寮), so I could catch my sunrise train to Hualien (花蓮). At parting, I presented his family with some fine pears, but I was wholly unprepared for his gift.

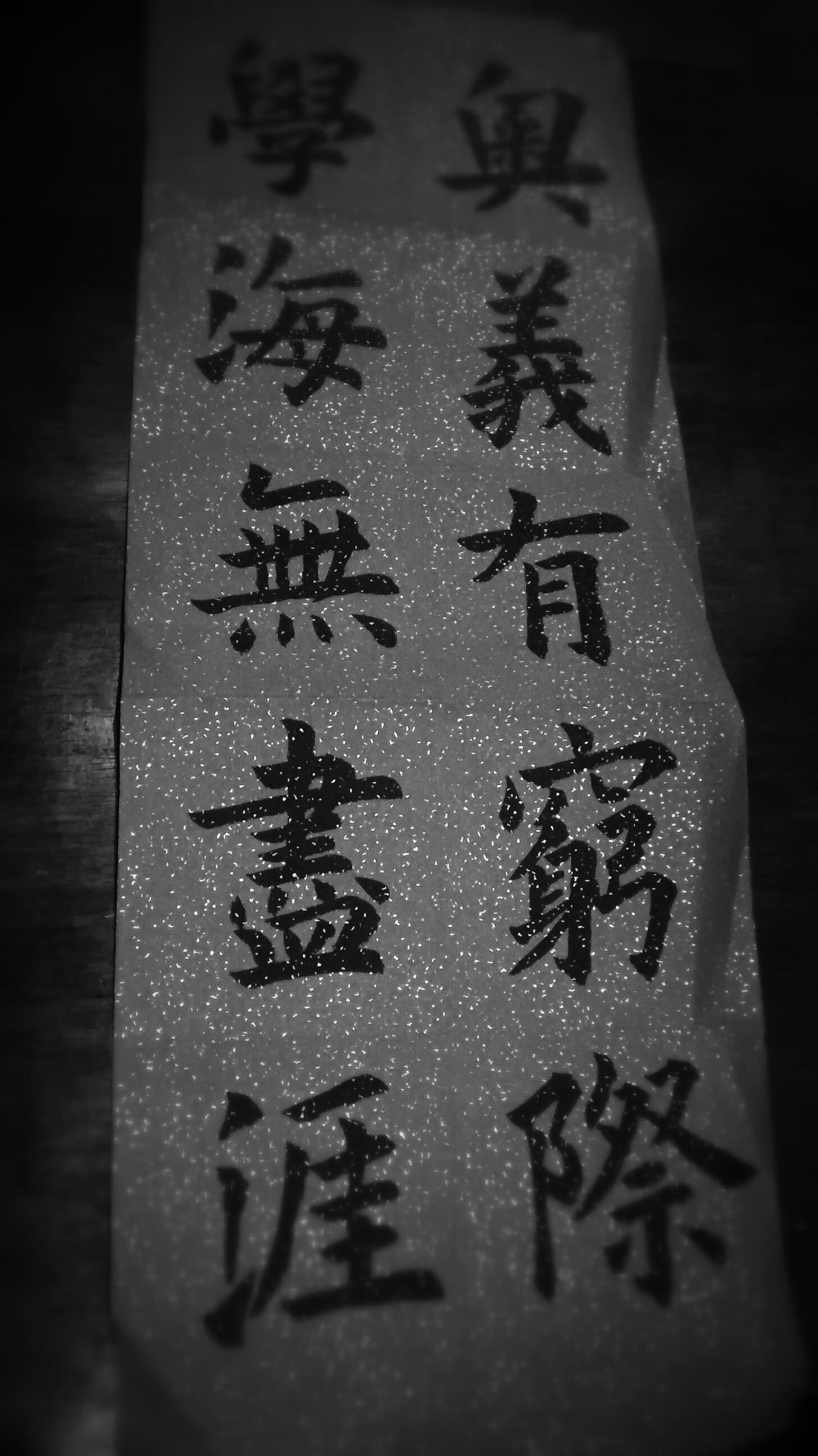

H is a master of calligraphy, having studied three hours a day for nearly ten years. He unravelled sheets of gold-specked calligraphy on red paper of my proper Chinese name (Aoxue, 奧學, “study of the unknown”), of my humorous one (E’xun, 餓巡, “hunger patrol”), and finally two Classical stanzas he had penned using each character of my name as the beginning of a stanza. The poem is read top-to-bottom, right-to-left, and will require your transcendence.

奧義有窮際

學海無盡涯

The unknown has no bounds;

the sea of knowledge, endless shores.

第十八章

During the mid-Autumn festival, the full moon stages a nationwide call for everyone to go outside and fry up some scrimps. It’s one of the few times a year I’ve seen the average Taiwanese drop forbearance to just tailgate. My family friend, whom I’ll call H, took me to enjoy one of these throwdowns with his large family, in the countryside a few hours north of my home at the ol’ sugar refinery.

H’s brother’s house is a well-to-do personal farm. The entrances are grated steel doors with glass panels, and the floors smooth stone. The house walls are typically Taiwanese: children, awards, some calligraphy and a large red-on-gold plaque of a four-character proverb about harmony. I always look at those plaques and wonder if, when you go to your friend’s house, you’re supposed to pretend to ponder its deep meaning for a second (“oh yeah, harmony, man”) and then get to drinking.

H’s brother grows feed for livestock and the rear of the house is reserved for fat chickens, fed a special sugar-enhanced breed of grain. As we sit down at a large lazy Susan for lunch, H’s brother demands that I prove my chopstick-wielding ability in front of everyone. He stands over me and his girth, also enhanced by his special grain, blocks the light from the hanging kitchen lamp. He hands me a bowl of rice. He’d grown that himself, too – “fragrant, don’t you think?”, and then waits for me to prove myself worthy.

I eat a smidgen in a way I’d grown accustomed to – it gets the job done, I think, but I’m reminded quickly that adequate is not in the vocabulary of an Asian father. “No. I will show you better.” He shows me a way in which one blade is always at rest, takes no arguments about its superiority and then shuffles to his bedroom for a nap.

Lunch starts without the dozing patriarch. There’s boiled wood-ear with shredded ginger, and a five-variety mushroom soup from vegetables grown on adjacent farmlands. Then, a platter of steamed shrimp that H’s other brother had raised, steamed fish in garlic sauce from the fish farm ten minutes away, and one of the fat cluckers from the backyard who has recently learned that harvest means sacrifice.

We go back to the dining room, thinking it’d be over, but now it’s time to go through the refreshers: white dragonfruit, kiwi, the apples and pears that I’d brought as a gift and glasses of high-quality, cold green tea.

Later, H’s brother wakes up and we chat for a while. I ask if he’s a “politician,” which he laughs and tells me has negative connotations in Chinese. He tells me how he’s the local town leader, and he is elected, but that he is in no way a politician. He’s, you know, just a simple farmer.

At dinner, they fired up the grill and then the black cars arrive. Our definitely-not-a-politician host happens to have a lot of friends with just-polished black BMWs who manage the local farm trade and finances. Out of every BMW emerges a heavy-set man with swelling calves, a sun-bronzed and chapped face, and a smile that pushes his thick cheekbones into his eyes. He heads straight over to a folding table that has been christened The Drinking Table, while the wife joins the other ladies inside to gossip.

From The Drinking Table, I overhear H’s brother more than once relate to his friends how I’d called him a “politician.” The whole table shakes with massive farmers slamming their beers down and laughing. I thought it’d fold back up. H himself is a teetotaler, and after we’ve eaten his discomfort at watching his family collectively redden gets the best of him and it’s time to go.

As I think is only polite, I hug the host’s wife, which leads to catcalls from the Uncles. “Hey, the foreigner is hugging your wife.”

I’ve been conditioned by mafia movies to be disconcerted when a bunch of Uncles are jokingly offended. In the movies, some young guy will make the mistake of thinking he’s earned the respect of the elders, accidentally crack a joke that mildly displeases one of them, and then find himself on the receiving end of a pant-shitting stare. Usually the tension is broken with a “I’m just fuckin’ with ya,” but you know the young guy doesn’t sleep that night.

But I’m not rattled. Earlier, H’s brother had told me about a new app in Taiwan where people could get groceries delivered to their house. My anxiety disappeared as I watched his bear paws thumb through a silly phone app, gawking at the features. He’d even texted me an emoji, a thankful bear, and I don’t believe anyone who sends melodramatic animal stickers could really be frightening.

H has let take part in his family celebration, and I’m thankful. I believe myself lucky to even have these people to celebrate the festival with, thousands of miles from home. My friend tells me there’s a now-trite Tang dynasty poem about the full moon, that all Chinese learn:

床前看月光,Before my bed, moonlight 疑是地上霜。like frost on the ground. 舉頭望明月,I lift my head to gaze; 低頭思故鄉。lower it, and think of home.

To give you a sense of its banality, it’s like finding solace for a life decision in Robert Frost’s poem about roads less traveled. But I can’t shake the feeling.

第十七章

After my mother left I packed up and moved out of the city center to an old sugar refinery. It’s planted in a few square kilometers of banana trees and small palms, between an abandoned railway station, a functioning one, a metro line, and a grim track of miniature rails that dead-ends in a pile of rocks.

In the daytime, it’s beautiful. They sell yeast-flavored ice cream to giggling children and play Taiwanese folk music on the loudspeakers and leave open to tourists a small railway museum with cast-iron relics. Railroad ties, spikes, fasteners, and large machines to fabricate them all. After a tour of the grounds in the hot sun, the yeast ice cream even sounds appetizing. But to visit only during the day is to practice self-deceit.

Many late nights I’ve passed through the open arch of the refinery to run or stroll. Not a peep; the few locals, at youngest septuagenarians, and in bed by then. The only lit path is beset by a wan fog, filtering the dim orange street lamps. Occasionally, the light will illuminate a signpost nailed to a tree: “Please, beware. This is a haunt for wild dogs.” That they actually used the Chinese for “haunt” is telling. For a while there’s only the bass, robotic echo of bullfrogs and yelps from a two-wild-dog tussle.

As I walk deeper I see white wooden houses in disrepair, some with small signs put up by the ministry lauding their bygone cultural significance. Now, I think, they serve as shelter for the four-legged. I see uncountable byways, pitch-black that say “slow” but really dare you, and I dare not. A gang of three wild dogs zigzags, crossing my path now and then, always trotting past and looking back warily, as if they’re the ones that should be frightened.

The tracks run parallel to the lit road, and when a train passes by the sugar refinery climaxes in terror. The train whistles lament and breaks the silence, high-toned on the approach and as someone once told me, purposely pitched at a dissonant minor third to warn passers-by.

On this evening, the small temple-of-the-refinery boasts its offerings. For the convinced, which is any local over the age of thirty-five in Taiwan, this seventh month of the lunar calendar is a month to ward off ancestors’ spirits by ritual feeding; the Ghost Month.

The wooden moulding of the shack hooks five red paper lanterns with hand-painted Chinese calligraphy. A soft light inflates each one, and in their muted red glow I see piles of brightly colored incense, fruit, and rice. The Taiwanese are not stingy with their giving, but later they will collect and eat it, so as not to waste.

T says during this month, more children are drowned in shallow water than any other because of malcontented spirits; I counter this cannot be true. He rebuffs, puffing air through his nostrils, as if prodding me to therefore explain the statistical spike in child deaths.

I think of the spirits as I’m on the lit road and for fifteen seconds I can’t hear the bullfrogs, or the dogs, or rustling, or anything. My chest tightens and I stand erect. I slow my breathing. I should turn around but I don’t. The corridor is alive with the whistle and if, say, there was an old farmer with a betel leaf habit who didn’t take kindly, well, when the corridor was deaf with the whistle, there’s the window to drag my wet, convulsing body into the Manila templegrass and disassemble me with the museum’s very own.

第十六章

When I picked my mother up from the airport in Taipei, she told me it was a miracle anyone let her through. “I left everything blank on the immigration card. Destination address, phone number, all contact information. They asked me questions and I had no idea. Why didn’t you tell me?” I had been negligent in giving her administrative details; just come to the airport, I said, I’ll take care of it.

The immigration officer, out of genuine concern, prodded her. “How will you survive here? You don’t know phone number? Nothing? Where your son live?” My mom had no answers; she’d tried in vain to pronounce Kaohsiung many times before and it wouldn’t come out now. She told the officer her son was just waiting downstairs, and that was the only information she knew to be certain, and at my mother’s conviction the officer finally relented. Thus began our three weeks together.

We saw Taipei; making use of her jet-lag early rising to see when nobody stirred. In the morning her head would hurt if she didn’t have Indian-style coffee, heaps of milk and sugar and an astounded waiter who was hesitant to give her more packets. We hiked Elephant Mountain and she saw all of Taipei at daybreak. To her, Taipei appeared a model, a target for a populated Indian city. If only the Indian government were competent.

Here, the streets were clean, the public transportation brimmed while it served. National monuments and public spaces far less paramount were spotless. Taipei locals cherished the few inner-city green spaces, and in one of these spaces my mom bought a bright, pink diamond kite with an exaggerated happy-face printed on it. Its tail was striped black and neon pink, and she flew it at dusk outside the Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall, her hands summoning the muscle memory of the collective Indian child. She was happiest in that moment.

We returned to central Kaohsiung a few days later, where I’d been living. Every morning she awoke before me, and the water boiler’s hiss and pour for Ceylon black tea ensured that I awoke shortly after. We’d visit the park in the early mornings when I’d run and she’d “power-walk,” or whatever term now best describes what compelled her to throw her arms every-which-way.

One night, after the typhoon hit, we went to ride public bikes at Central Park, but a paper sign matter-of-factly pronounced: “Due to the Typhoon, there will be no bike rentals.” We went back to fetch the kite.

A dark, purple sky in post-Typhoon winds is the worst time to fly a kite. But I spent nearly an hour flaying my hands with kite-string to try to get Pink Smiley Diamond back in action. I’d have given up if it wasn’t for a small girl who clutched her mother near me. Some disability caused her to laugh uproariously every time the kite faltered and crashed into me, or slid into a puddle on the ground.

But when the wind allowed kite a few seconds of lift, she stood fixated. And when it crashed, and it always did, she would laugh with the same furious enthusiasm. Thankfully, the hourly water show started and my all-too-real performance as the village’s moronic kite-flyer was supplanted by timed fountain bursts. I wrapped it up.

We lived like this for a week and a half before going to Hong Kong to renew my Visa. This fragrant harbour was a blur; filled at all hours by a nightmarish throng that shopped as if in perpetual bonanza. The metro was covered with ruddy tiles. The train interiors were dirty metal, reminiscent of New York’s subway.

We’d eat well. For the five days we had in Hong Kong, I took my pleasures from 添好運, the self-professed Dim-Sum specialists. Steamed honey-egg cakes, 潮州粉果, Chaozhou-style dumplings with pork and watercress that split at the slightest pressure from the teeth. My mother was less interested in the food, and after meals she’d be eager to haggle for trinkets, while I retreated to a cooler place to work. She took her pleasures from the sights above all, and I begrudged her a few photos at the smoggy Victoria Harbour.

I was happy to return to Taiwan, to spend one more day with my mother there before she returned home. Near the airport in Taoyuan county, we stayed in a room with white tiles, high ceilings, green metal cupboards and concrete walls that reminded us of my grandparents’ home in India. No better place to take an afternoon nap.

In the morning we ate the guava we’d bought the night before from one of Taiwan’s lecherous fruit-mongers (these vendors are gangsters in disproportionate numbers), and I saw her off at the airport. I was grateful for the companionship. My mental health had tattered from the solitude before she came; her visit patched it. She escalated her requests. “You can always come back,” she told me. “You should. You have to. By December.”

Yes, I think I will.

第十五章

I’ve got a black eye, courtesy of a Taiwanese 巨人, a giant. We’re eye level but he’s a lean 92 kilos, about three weight classes above me. I’d seen him often at the Muay Thai gym, smacking a sand bag or showing a high schooler how to box. Over the weeks as I watched him, I knew we’d have to fight one day. There are only so many people here above 80 kilos. Hey, you’re big. He’s big. You’re gonna fight, right? And when these bouts go down, the entire gym saunters over to watch. It’s a shame they don’t serve popcorn.

He was always smiling, in a generous way that unnerved me. He called himself a 胖豬, a piggy, but with his leanness he was more like a wild boar. We decided to go three rounds, no throwing elbows or knees. We stepped into the ring and touched gloves. During round one, as was customary, we felt each other out. I had a reach advantage, and he had the forward momentum of a locomotive. Even when I landed a power shot, he would keep smiling and advancing. He wanted a smaller gap where a salvo of hooks would hurt the most. In the first round, I wouldn’t let him in. We spent the round circling.

In round two, things heated up considerably. He moved faster and landed more hooks. He threw a few reluctant head kicks but didn’t have the right timing, and I surmised that he was an expert boxer but only a recent disciple of kickboxing. To compensate, I started hammering his front thigh. At two minutes in I was ready to declare this boar roasted.

But then I found myself in a corner, and the hooks came. Left cheek, right cheek, stomach. He punished my skull and ribs. I pulled my forearms up to my cheekbones in defense, and through the small gap, I saw him smiling. Each swing came fully from his torso, and started to overwhelm me.

A sharp knee or long elbow would let me bail from the corner, but we’d agreed not to throw those. I started to sway a bit and lower my hands. They teach you to keep a rhythm when you attack, to help you with your breathing. But in the midst of his strikes, my internal timing went off-kilter, slowly synchronizing to his offense instead of my own. He was still smiling. I felt dizzy and that would have been it if the timer hadn’t gone off. I breathed in deeply, raised my hands behind my head and tried to muster my consciousness. There was still one round left.

I couldn’t out-box him, so I’d have to wait for him to get greedy with his hooks. Then, I’d introduce my left shin to his stomach. So when he came again, smiling, I waited. He started hooking, left, right. I had a limited time to eat those while my energy drained. I forced myself to pick up my left leg and turn my hip into his stomach even though the gap between us was too small for that to be effective. But he was startled at this southpaw maneuver and jumped backwards, falling into the length of my shin. He winced, still smiling, and I followed up with a left straight that knocked out his contact lens. What an inglorious end to the round.

I continued sparring with whatever challenger approached. Almost fifteen rounds later, I was beat. The fibers of my upper thighs felt crushed, and I was twitching from the exertion. I fell backwards into the ring while my sweat soaked through the tarp covering. My friend joined me. You know, he said, I feel high when I look at the ceiling. I slowed my breathing stared at the iron trellis above. There were masses of unused power wires bouncing in the wind of the fans, tires supported by chains, and ropes criss-crossing the girders. Total chaos.

But I did feel a pleasant lightness with my head against the mat, and I dissolved into the muted drone of our coach’s favorite electronica.

第十四章

I’ve been in a rut. The eccentricities of Taiwan flooded me and then receded, and I let out a deep sigh this morning. Where I once delighted in eating a strange animal, or watching the locals’ gestures, or finding the metropolitan library, something reductionist in my soul switched on and now that library is just a damn collection of books.

It’s to be expected, I suppose. My honeymoon with the island is over. I’m reminded of summer days in South Carolina’s dead heat, at the kitchen table, too hot to go outside and no more ice cubes in the freezer. Nothing to do but rest my arm on the chair adjacent and stare at the quiet pines outside.

I wonder if searching for the novel and the foreign is just a distraction. Better, an addiction, the stimulus being the unfamiliar and the high, reveling in it. Being uprooted is like heroin. But then your tolerance increases, and the surroundings seep into your pores, and you realize there’s still life to attend to. To seek companionship, and a purpose, and all that shit.

Under my bathroom’s fluorescent lighting, favored illumination of jail cells and mess halls, I stood for an hour, blankly staring at the grout between the tiles. If my boiled brain could think of leaving, my legs wouldn’t have obeyed. The hot water didn’t purify or relax me. Instead, it dehydrated, and trapped. I thought my flesh, bones, and hair would congeal and like in an cartoonist’s acid trip, this human lump would flow into the drain, and that would be that.

I remembered my ex, who would stand there for so long, clutching the ponytail draped over her left shoulder and staring at her reddening feet, nestled in the coil of her mind, no desire to escape. She’d step in every day, accustomed to the vacuum, expecting the release. I believe with experience it can become a meditation, but I haven’t yet learned to give in. When the steam wrests control of my faculties I want to scream, but even then it suffocates. You can’t win.

Nobody but me will be surprised that a hot shower didn’t murder me, but I feel I must clarify: I did survive. The water heater behind the lattice of tiles eventually started groaning and like a host tired of the dinner guests, it grew colder and then cold. Get out.

第十三章

“Where are you from?”

A Taiwanese man can’t help but ask. English here is a prestige language, and anyone with my doe eyes is going to find themselves fodder for the curious. But I’ve come to realize it’s more than a chat; it’s a game of tongues, and they play to win.

The Taiwanese moves first. An attempt to assert dominance by opening with a short English sentence. The quip will be drawn from the same tired pool of, “How long in Taiwan,” “Where you work,” and “Have a nice day.” My counter could be a gracious response. Yea, we could parlay. I could feign amazement at his English while he subtly erodes my faith in my own Chinese.

But I’ve found the trump card, a way to wrap up the conversation in seconds. And by midday, in the sapping heat, when I’m tired and just want my iced tea, I’ll use it. It’s simple, really. Respond with good Chinese.

You’d think that’d lead to a real discussion, a talk worth having. But it’s murder on their pride. The askers aren’t interested in you. They’re there to prove to themselves and to bystanders that their cosmopolitan minds can flit from Chinese to English. They expect my long arms to unfold in an embrace. To shed a few tears, to be oh, so thankful that a prince has arrived to take me away to an English-speaking haven, if only for a moment.

But I, too, am prey to pride. And when I respond to their question in the national language, I relish their falling face. When I ask, “Where are you from?” in Chinese, continuing to wonder about where they were raised, and if they live nearby, and what they do for a living … man. You’ll never see anyone so quickly put out the flames.

They think I’m implying I can’t suffer their English. That’s not what I mean, of course – their English is always passable and sometimes even cutely affected with American diphthongs. But when we’d both like a chance to practice the other’s native language, and it’s too troublesome for him to hold a bilingual conversation, we’ve gotta wrestle a bit at the start. To pin the language for the match. And the loser is always sore.

第十二章

The tension between P and I thickened. We used to switch, one day English, one day Chinese, but a few days ago he suddenly refused to uphold the Chinese end of the bargain. He exclaimed he would continue to refuse, because speaking English in public made him feel like a 要人, a VIP, and that he would relegate our Chinese conversations to closed-room only.

I’d had it with his caprices, and so in a silly détente, he spoke to me in English and I to him in Chinese. Neither would improve. I posted some ads for a language exchange for when I’d move out the next week, partners who knew the meaning of give-and-take. And I’d be glad to be rid of his lunacy.

Last night, as I’ve seen too many times, the aura of mischief that surrounds him by day turned sour. Yesterday when I walked out of the shower he was waiting on the bed. He welcomed me into the room.

“Aboriginals is useless.”

No, P. First of all, people aren’t ever useless; humans simply exist. They deserve respect. And “useless” is for objects.

“Yes. But I really think Aboriginals is useless. Do you know? They…are…so…useless.”

As if his unfettered racism wasn’t enough, he enunciates each syllable slowly to make sure I’ve understood his English. I’m unsure where his vitriol comes from; he’s not Han Chinese, speaks Taiwanese as his native language, and prides himself on being a local. You’d think his genocidal attitude would’ve been beaten out of him by his family.

Before hitting the lights, he told me if he had the power he would strike all Japanese announcements from the Metro’s announcement spool.

“So all Japanese will leave Taiwan. Do you know? I hate them.”

I’m not sure how I failed to see the signs. I misstepped when I didn’t recognize his cackle as something more sinister. When day after day he would constantly rant about wanting sex and would sometimes call his online girlfriends ten times in a row when they clearly didn’t want to be bothered. Unaware that nobody in this world wanted to put up with his character.

He continued to babble. “Why they call economy class? They should just call poor class. If poor people is smarter, they don’t be poor.” Was this monster unknowingly channeling Ayn Rand?

He asked me if I had read downstairs. I didn’t want to answer his questions. No, I didn’t, P. I’m going to sleep.

“Why are you lying? I know you read downstairs. I can see the camera. That’s my right.”

Time to leave. Had he actually asked the hotel staff to see security footage? Had they let him? I needed to focus on writing software, the reason I came to Taiwan, instead of rooming with a psychopath, spending my free time dreaming of repartées to his warped world-view. I thought of slipping out, chalking up the money he owed me to a truly lost cause. But then I thought about meting out justice, and I wanted my money back, now.

He was on his phone, no doubt aggravating some poor girl as he tried to fall asleep. I startled him. Hey, P. Give me my money back. I’m leaving.

“Now?”

Yes. I gave you a lot of cash and I want back the days I didn’t use. I’m not living with you anymore.

I spoke and didn’t recognize my voice. It was mixed with something unwavering, powerful, precipitated by adrenaline. He looked at me and I saw his eyes widen. He sat up immediately and glanced me over. I had forty kilos on him, a rectangular purple bruise covering my right bicep and fresh amber splashes on my left hipbone and collarbone from sparring, and for the first time I saw him frightened. He quickly pulled out his wallet and refunded my cash.

“But you have to leave now. Otherwise I can not sleep.”

As if I could have spent the night there after seeing who he was. I needed a plastic bag to carry the bananas I had bought earlier that day. They were practically worthless, 15元, but I didn’t want to concede a single trifle. I called reception and asked them to bring up a plastic bag. I couldn’t remember the word for plastic; 你們可以來一個玻璃袋嗎 , “Can you bring up a glass bag?” Reception was confused.

I saw P sitting on the bed, grinning, relishing in my struggle. I told myself I couldn’t be the confused guppy in our final encounter. I had to walk out knowing I could do everything myself. I racked my brain, and then suddenly I remembered. 塑料. Plastic. Reception instantly understood and told me they’d be right up. P’s face fell. There was nothing I needed him for.

I looked at the clock: 3:27am. I packed my belongings into my yellow Osprey in less than one minute and walked out the door, down the elevator, and onto the humid Kaohsiung night. The pimps were out like hyenas, following me for short distances on their scooters to ask if I wanted a 小姐, a little miss. I was crazed from my victory and refused them with such exaggerated courtesy that they were left speechless.

I found the first hotel close-by.

“Sorry, no vacancies.”

I kept walking along the largest road, turning into alleyways to see who’d put me up for the night. Finally, on the 12th floor of a building, I found relief.

“Yes, we have vacancies. One thousand 元.”

Why I bargained her down that night, with zero leverage, I’ll never know. But she conceded, watching my veins pulsing and my grin, no doubt thinking the sweating fool in front of her, a yellow bag on his back and bananas in one hand, had walked miles and would walk miles more for a good deal. It was just in my face. I felt I could have taken anything from anyone at that moment.

第十一章

P is exhausting my patience, petulant creature that he is. He comes from a criminally rich family and I now realize the contempt he has for most people comes from being coddled and untouchable from an early age. His family’s business put local politicians in his father’s pocket, and at his expensive private school, he would often test teachers, daring them to discipline him. No doubt, the thought of his father permanently setting them straight loomed in their minds. “They could not dare,” P told me, proud.

Today we sat outside at a tea shop, while he smoked, barely drinking. He saw a waitress with a broom coming to sweep the area, glanced at the ashtrays to his left, and flicked the cigarette butt to the floor in front of her. She raked it in and asked him why he couldn’t have just used an ashtray. “Oh, I didn’t see.” He saw.

–

I’ve found a Muay Thai gym I can visit regularly again. Though both clichéd and self-serving, I believe habitual martial artists are both determined and respectful, in stark contrast with the cat that’s been following me. The facilities are much closer to those of Thailand than I expected; the torch-hot interior is fueled by the Taiwan sun through jail-bar openings. The shower, a misnomer, is actually a plastic bucket on a concrete floor with a single rubber pipe that trickles chlorinated water from a tank. But it’s a fitting end to the brutality of the workout. Don’t I go there to become stronger?

After my workout I had a few plates of 白切雞, cold-cut chicken with ginger, and a 竹笙紅棗湯, bamboo-pith red-date soup in a rich chicken broth with leg. The bamboo-pith is actually a mild-tasting fungus that’s light, porous and spongy. The pith is cut into little sleeves and you can put your tongue in one, and feel the little holes cover your tastebuds.

I also recently had an enormous 芒果花雪冰, shaved-ice with fresh mango chunks, which was topped with the most fragrant, fleshy mango I’ve eaten outside of India.

–

When I walked out of the shower today P was sitting on the freshly-cleaned bed, wetting his lips with his tongue, and told me “I will be perfect in my next life,” before turning back to his phone. The non-sequitur be damned, if he actually believes in karma, he should realize just how forsaken his lot will be.

He told me today: “Do you know why I walk around like I … how did you say, own, everything? Because money can buy it.” I’m sure he would have understood the phrase “money cannot buy respect,” but I can’t impart him any humility so I’ve stopped trying.

Today he took his sweating iced mango tea and put it on my closed laptop. When I yelled at him, he quipped “it’s doesn’t matter” without moving his eyes from the game show he was watching. I found this so unspeakably rude that if I were Hannibal I would have eaten his liver, cru au sel, on the spot.

So I’ve decided to split from him, slink away if need be, in twelve days when we’re cash-even. I don’t want my experience in Taiwan to be eclipsed by his dark companionship.

第十章

P told me the Taiwanese custom is not to converse at dinner. From watching other groups eat, I know that’s a lie, and he’d just rather text girls online than subject himself to my unending questions, like “how do I talk about multiplication in Chinese?” I told him chatting with friends online counts as conversation, but I suppose no culture is immune to Phone-at-Dinner syndrome.

At the Vietnamese restaurant I habitually visit, there’s a young girl there, no more than 14-years-old. She helps out her dad in the kitchen after school, and in the downtime watches our great American exports, like Spongebob. Sometimes while P is furiously texting (with a woman who is probably twice his age), we chat. She is sweet and teaches me to read menu signs. The night before going to Taipei she touched my shoulder and gave me a packet of shrimp crackers. “We are good friends!”

When I walked back to the hotel room later that night I saw her father talking to a guy leaning against a scooter. Another pimp. He asked me if I wanted a “小姐” (little miss) to visit me in my room, and when I tried to politely reject him by pretending I didn’t understand, he put the finger of his right hand through a hole he made with his thumb and forefinger in his left and starting thrusting. “You know, a little miss.” Yeah, I know. Christ.

If I’d said yes, I couldn’t eat at that restaurant again. As if the father would let me! I think it would break some deep cosmic rule of decency to hire a prostitute in front of his eyes not two hours after accepting shrimp crackers from his daughter. I also wonder if I appear so lonely and depraved that it looks like I’m in constant need of paid sex.

P stumbled into the room at 3 a.m. and woke me up with soft yelling. “e-shuen!” e-shuen!” can I have money?” He was clearly drunk and I gave him a few thousand yuan to make him go away. As I nodded off again, it struck me that he’d finally given in to our pimp’s wiles, the one with the Sultan-red mouth. I knew the price and what was in P’s wallet, so even with my money he was getting his wanton pleasures on credit.

I’ve seen enough mob movies to know that owing anyone on the salacious side of life is, shall we say, inadvisable. That’s when track-suits show up at your door, you lose a few fingers, and your pet gets shotgunned and thrown into a pool. As a little taste of what’s to come.

Hours later, when I woke up, I saw he’d vomited when he came back. A small streak started from the side of the bed and ended up in a pool of meat-sized chunks. Those were the dregs from his stomach, and I judged, not his conscience. When I saw the tiny packet of shrimp crackers on my night stand, I though of the girl, and I left the room cradling them. The whole thing was so sickening, and I wanted to be alone with my crackers.

第九章

When I got back from Thailand, P greeted me at the train station in the same way he sent me off: a cigarette in one hand and smiling like a fool. I handed him the cartons of duty-free cigarettes I’d promised him from Thailand, his favorite brand. He was hot to smoke one.

He lit it without ceremony and puffed. “Mm. I think it’s so soft. Not the same.” I was surprised, since the box said “Made in Japan,” the manufacturer’s origin, but then I don’t know anything about cigarettes. “No, do you know in other countries. They use different, how do you say – 菸草, yancao, tah-back. To-back-oh. Because Thai people are weak.” He drew another stick from the box and gave it to our friend the pimp, who was leaning against his scooter. In sprightly Taiwanese they agreed the Thais didn’t know a damn thing about having a good smoke.

Lesson learned. The Thais will use hand-grenades in anti-government protests, but have a womanish taste in tobacco.

We walked together to reception. The girls at the desk were giggling to each other and the more forward of the two asked my name and then if she could call me 巧克力 (Chocolate). As probably the darkest man to have crossed her starry eyes, and this name being decidedly sweeter than the Brown Cows, Brown Bears, and Choco-Tacos I’ve endured over the years, I yielded. P rushed to defend, but I know his sense of racial justice turns with the clock. Hours later, as I worked downstairs in the restaurant, a Japanese man entered and P cried, “He is a Japanese! Do you know? I can tell! Arigato!”

–

On the metro, I’ve started to read 戰爭遊戲 (Ender’s Game) in Chinese. Yesterday I absent-mindedly seated myself in the disabled section. But when I realized it, I didn’t move. It is appropriate: I am disabled here. I cannot read a street sign without pausing. I cannot resolve a shelf of bottled teas at the 7-Eleven into their elements, to find one without sugar. My Chinese, to buy and to ask, is excellent. But who wants their words to be curbed to talk of commerce? I want to talk about the abstract, and about our nature.

It will take me nearly an entire year to slog through the book’s nearly four-hundred pages. I attempt to thread the words I’ve read into everyday conversations, but the vocabulary of of Ender’s Game resists. For example, 蟲族: insect-race creature. It’s hard to use that coolly.

“How’s it going?”

I’m great. Hey, how ‘bout them insect-race creatures?

บทที่ 8

The mornings in Bangkok orchestrate like a rainforest biodome. At 4:30am, mute chirping breaks the whir of the in-room air conditioner. Then, pairs of throaty birds converse, pausing as if to make sure I’ve understood. Their conversation picks up, the one telling and the other feigning interest as if to remark, “Oh yeah? That’s so interesting! How did that happen?” I wish I could tell them I don’t care.

I’m face-down in my bed as tropical hooting breaks out on the periphery, and soon after all roosters in Bangkok murderously herald the sun. By 5:15am I’ve lost any hope of sleep.

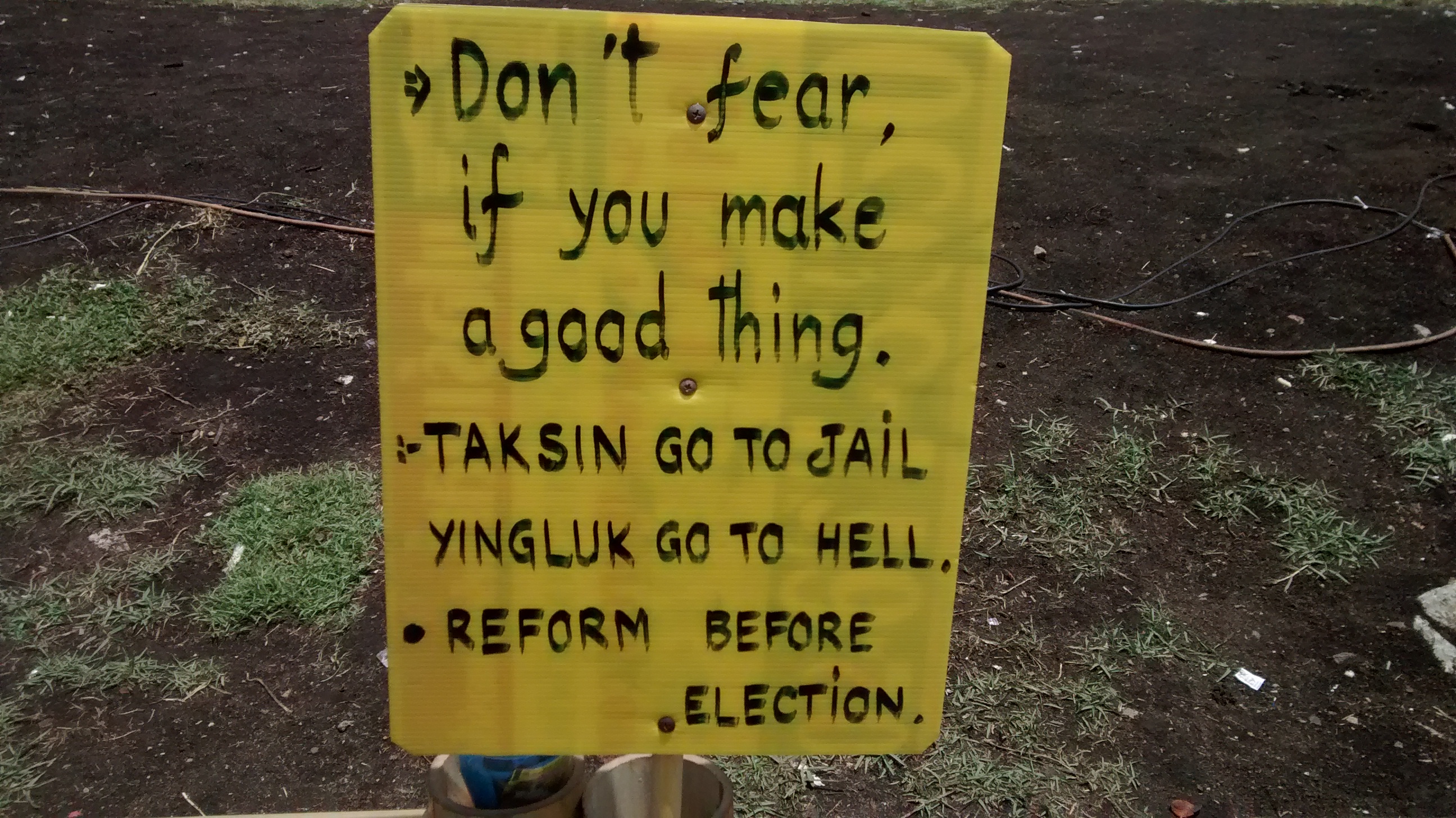

I heard on the news that a policeman had been killed by a hand-grenade thrown by a protester (many of whom were subsequently shot) just a few days after I visited the royalist camp at ลุมพินี (Lumphini) Park. In fact I was simply looking for scenery beset by Bangkok’s skyscrapers, but when I arrived at the สีลม (Silom) metro station and saw the entire park had been permanently camped out, with medical tents and goods for sale in a strange mix of fair and protest, I wanted to see. By chance I was wearing royalist attire, a bright neon yellow shirt. Silence and brown skin make for an asset in Thailand so I walked through the security checkpoints, pat-downs and metal-detectors without scrutiny and walked around.

There were angry signs, some chanting and a man on stage fomenting resistance, but I wouldn’t have predicted the park would see violence any time soon. After all, in these tents lived children and the elderly, and they were still Thais. Beaming and humble.

I saw eight bouts of professional Muay Thai at the new Lumpinee stadium – the old one next to the park had been razed when I got there. The afternoon billing didn’t have a single fighter over 130lbs, and yet their torsos are so ribbed and sinewy, that my friend said he wouldn’t take less than $5 million to stand in the ring for a standard bout of five three-minute rounds. That’s dollars, not baht.

The live music starts slowly in the first round. The fighters feel each other out, throwing jabs and teeps (foot-jabs) to test the other’s range, and mettle. At round two, thick legs bludgeon torsos, and they lock heads in a clinch, hoping of landing a knee to the solar plexus. By rounds four and five the music is frenetic and a knockout is likely – I saw three that day: one sharp left hook, one shin bone to the skull, and an elbow driven upwards into the opponent’s chin.

I spent days in Chiang Mai and Phuket, but I won’t write about them. Chiang Mai was boutique-touristy like an artsy Southeastern US “-ville”, and Phuket would rape you for money and dignity if it could.

My friends’ flights were hours before mine so I thought I’d catch them before they left for San Francisco. Without putting in my contacts I walked into the room next to me. The new house had empty wood floors and walls chock-white with construction dust. I thought the bedsheets wrapped a friend sleeping late, but my blurry eyes betrayed me and the sheets deflated when I touched them.

I saw a blue mass on the floor that could’ve been jeans and thought they’d be downstairs having tea. We’d have our last breakfast together over minty Ceylon black. But I called and no response, and I realized it was just a dark blue towel. Bangkok was full of sounds this morning, but none I wanted to hear.

On the way to the airport I found a rooster and tried to kill him, but he ran. Damn chickens.

บทที่ 7

In my Bangkok flat I’ve just set my clock an hour back and I’m glad to have the extra hour to write.

I got to Suvarnabhumi early. My dad, Sanskrit scholar, told me the name means “Golden Earth,” and I think it fits the airport’s grandeur. I took the Airport Rail and BTS (Bangkok Mass Transit System) to a stop on the dark green line. It’s right by the Khlong Bangkok Yai, a canal off the large Chao Phraya river that dumps into the Gulf of Thailand.

The Thai BTS is clean and runs well, and reminds me of Taiwan’s. There’s no excuse for the US’s only legitimate metro system, the New York Metro, to smell like urine and taste like despair, shamed by a country with a lower Human Development Index and summer temperatures sometimes thirty degrees higher.

Our hosts had marked the address wrong so I had to navigate the impenetrable but beautiful Thai script. In one of the few times I haven’t learned any of a country’s language, my failure to invest quickly became apparent. I started wandering around alley-ways with my enormous yellow backpack, soaked in sweat and staring down young children because the heat was irritating me.

I asked a group of Thai teens for help, and one of them gave me complicated directions in Thai until I presented such a vacant stare that he told me he’d just take me on his scooter. But since I was too heavy, I had to drive. I dropped him off at some random intersection, clearly not the place, but he had run out of patience. I asked another man, who took me on his scooter at break-neck speeds on a major thoroughfare, and eventually got me where I needed to go. Exhausted, I thanked him with some baht; he returned a wai.

I went out for a two-hour traditional Thai massage, which was four times less expensive than in Taiwan (150฿ per hour), and (chastely) more invigorating. When I entered the stop, platonic in appearances, I was asked to choose a girl. If I wasn’t having sex with her, I didn’t understand why it would matter, so I just waved my hand to indicate whomever.

She scrubbed my feet with a coarse bristle brush and lime soap, and then led me upstairs to a room with two thin cots, a small television, and muted walls. Twenty minutes after she started massaging my lower body she unshly asked if I wanted “go boom boom,” which I sheepishly refused. I don’t know why I’m embarrassed to refuse gratification from a Thai hooker. As if I were somehow obliged.

She continued flipping me over in various ways while she watched a moronic game show and I stared at the ceiling to fight any rise. The last thing I wanted was to have my body betray my insistent “no”s. R. Kelly and I find ourselves in similar predicaments.

She asked me a full five times before our two hours were up. At the very end she cradled me while massaging my head and neck and that’s when I was especially glad not to have accepted her offer. A relationship that goes from paid sex to maternal love in the span of an hour is something I never want to experience.

Afterwards I walked down the street, hungry and thinking I’d make the journey to a well-rated TripAdvisor selection. But it was a joint run by an American, and since my two white friends were arriving tomorrow, I knew one visit there had already been tacitly scheduled. So I stopped in at a distinctly Thai joint and pointed at the most expensive things on the menu because anyone knows that means good meat. For 150฿ I ate three plates of duck feet, duck neck, shredded duck wing with mushrooms, rice and hot soup while the restaurant owner stared at me in disbelief. I didn’t speak a word. When I left I gave her an inappropriate wai, for having watched the carnage.

As I continued I noticed a few signs with Chinese characters and I felt bizarrely homesick for Taiwan, where I’d come from and had been living for only ten days.

We reach for the familiar. In my bag there’s one shirt I forgot to wash. It smells like our hotel room in Kaohsiung, like Parliament cigarettes, and sweat, and P.

第六章

I must present a brutish figure as I grow darker and more disheveled. The Taiwanese, nearly all Han Chinese, are a hairless race and so I can’t find either a real razor blade or a barber to wield one. At some point the seventy-year-old ladies who take the mid-day metro are going to start shuffling to the other side of the platform to avoid me. You know, like suburban whites do to black people in America.

The tea shops here are first-rate. Every day one of us comes back with an iced 鮮柚綠茶 (fresh pomelo green tea) or 蜂蜜綠茶 (honey green tea) for around 50元. Fresh means fresh. You can taste the pomelo fibers. I think I’ve eaten at all the nearby traditional-fare joints, but I’m not tired of them.

A favorite past-time of English speakers in the Sinophone world is to find horrific sign translations. “Do not fall on the slippery,” “eat please toilet for practice,” and so forth. Here in Kaohsiung, almost nothing is translated so opportunities for comedy are few. But allow me to regale you.

One is 奶油獅主題館, or the Butter Lion store, which sells school supplies for little kids. I think Butter Lion is the most idiotic name I’ve ever heard. The official explanation is that one day a bear was walking down the street and got butter-cream-pied in the face. And so he became a Butter Lion. Right. This cock-and-bull story infuriates me and every time I pass it I take it out on P.

Do you see that, P? You can’t have a Butter Lion. It’s totally implausible.

“what is implausible mean?”

I mean it doesn’t make sense. You can’t have a butter lion.

“why are you angry. it’s just name.”

If I had a kid, I would refuse to buy any school supplies from Butter Lion.

“Why not, dad?”

Because, honey, it doesn’t make any goddamn sense. We’re going to Target.

The other is 油廠國小, or Oil Refinery Elementary School, a stop on the Kaohsiung metro that conjures up a school struck by the Exxon Valdez. A classroom full of five-year-olds knee-deep in oil, leaving black fingerprints as they leaf through textbooks, their little throats sputtering. During recess the kids would writhe around on an oil-soaked field, like unfortunate seal cubs. I bet Oil Refinery Elementary has the losingest little league team in history.

Last night while I was showering P burst in, gesturing wildly about how he thought his stomach-ache hadn’t left for a few days and so was probably cancer. In that instant, listening to his hypochondriac prattle, I was wet and fully nude. Only a transparent glass pane separated us. He went on for minutes. You don’t have cancer, P, and I’m completely naked. I wondered what the hell was wrong with him – it wasn’t the cancer – but as they say, what is seen cannot be unseen. He calmly walked out when I finally reassured him. I kept showering for a while afterwards in a vain attempt to reinflate my personal space.

第五章

We had a brief conversation with the pimp outside our hotel. Or should I say, P chatted with him in Taiwanese while I drank my liquid 酸奶 (yogurt). Every once in a while our friend the pimp turned his bright red, betel-leaf-stained mouth in my direction and asked me if I was from America. “America? Good. You want, so cheap!” I almost felt bad declining him so many times, but my upbringing notwithstanding, I’d pick up a disease faster than he was going to get mouth cancer.

P is keen to strike up a conversation with the seediest characters, and I think it stems from his genuine lack of judgement. He believes every soul deserves the gift of (his) conversation. Who knows, the guys on the street corner cat-calling night after night might enjoy the change of pace.

His only intention is companionship. He could never put any of his ludicrous talk into motion, but he enjoys the shock of practicing his “sex-English” with me. Around actual women he’s respectful and bashful. He’ll often pester me to strike up a conversation with random Western-looking travelers to practice English.

Today I went to visit a pair of the allegedly most beautiful metro stations on earth: 美麗島站 (Formosa Boulevard Station) and 中央公園站 (Central Park Station). Formosa Boulevard Station has a large stained-glass ceiling which looks lonely in the mid-afternoon.

But Central Park Station deserves its title. Its staircase is nestled in dense, paleolithic ferns that lead up to a jarringly verdant park in the middle of the city. It’s inhabited by a few geese.

Tonight P and I had 魚皮湯 (fish-skin soup) peppered with a few scallions and ginger strands that really hit the spot. Steamed 地瓜葉 (sweet-potato leaf) and a few typical rice bowls like 叉燒飯 (barbecued pork rice) completed the meal.

I’ve never seen P walk past a beggar on the street without dropping a coin or two in their plastic alms boxes. Tonight in an especially poignant moment for his level of English, he confided,

“because i want god to keep blessing me, do you know. we are all humans, do you know? we are all humans.”

第四章

P’s a slim man – boy, really, and tall for a Taiwanese. He’s dark, with an aboriginal bone structure and weighs only 120lbs. You can see a carved valley where his cheek fat isn’t. His eyes are sunken but bright and he sports a thick black crest of hair that somehow keeps its figure in the island’s humidity. I could place him as-is in a Museum of Natural History diorama with a spear and a stuffed saber-toothed and no-one would be the wiser. That is, if he wasn’t constantly shifting his eyes and rubbing his hands. I think the museum-goers would quickly become the ones on display.

His first statement on waking: “i found that girl delicious. can i say that.” He’s probably been pondering this question the entire night. No, I tell him, that’s only for food. I can’t bring myself to teach him more innuendo than his adolescent brain already generates.

We went to 後驛站 (Houyi station) to get P’s ID card. The station is nearly empty; we pass the time tossing little blue RFID ticket coins to each other and I find out he’s near-sighted, so he drops them constantly. We had lunch at a close-by duck-shop, where tens of braised ducks lined the perimeter of the kitchen. I had some 鴨血飯 (duck-blood rice squares), and 鴨湯 (duck soup). I wonder if the duck-blood squares are served only to fulfill the East-Asian tradition of eating what ails you, because they have no taste. In any case, the hot, gelatinous Taiwanese soups are working wonders on my sore throat and certainly redeem the few misses.

We had a typical 牛肉湯 (beef noodle soup) dinner and P smoked his twelfth cigarette. He’s promised to try to quit by lowering the number of “sticks” he smokes by one, every day.

After dinner, I was impressed to hear him articulate a story of mischief and guilt.

“can i tell you a new secret. i was farting in lift. there was three people they were smiling at me. then i was smiling at them. i’m feeling guilty because they was smiling but i could not take back my farting because it was already release. but if i feel like that way again, i must do it in the elevator. i am sorry. but i must do it.”

That’s OK, P. We are all beholden to our own biology. I hit the lights to sleep.

“do you want to get hooker?”

第三章

P is going to need a lot of schooling in Western propriety. We went downstairs to breakfast today, where the typical fare of meat-and-eggs was colored by a selection of 燒賣 (shaomai), fresh 番石榴 (guava), a watermelon with yellow flesh, and 冰都將 (cold soy milk).

Over this, P rubbed his hands together and looked around lecherously. He raised his eyebrows at me and gestured with his head to tell me I should check out the girl not three feet away from our table. I told him I wouldn’t be so damn obvious and he exclaimed, “why not? your chance to have sex for free!” So, now he knows the word for “pervert,” and I the word 色狼.

We set a schedule to first study English and Chinese separately, and then review together, because when we’re in a room he cannot stop talking. He is becoming stingy with his Chinese, effectively ending our conversations with single-word replies. So I yelled at him. How else can I learn?

We went to the 高雄六合夜市 (Kaohsiung Tourist Night Market) to get 水餃 (dumplings) at 4.5元 a pop. And that price! We ate sixty between us. While P was busy shouting at people in Taiwanese, I couldn’t help but notice the word 印度 (Indian) being thrown around every other sentence. This place is more homogeneous than Oregon and I wonder if fate wouldn’t throw me a bone in the form of a single black person.

At the end of the night P said, “do people in America rub hands in winter?” Yes, I told him, it’s a universal way of warming oneself. “good, because I will do that in winter. not because cold, so I can prepare.” Prepare for what, I hesitated to think. “prepare to grab!”

第二章

I woke up at 6am this morning and did some squats; still regaining flexibility in my ankle from my soccer sprain. While I was taking a shower I looked out of the window and saw a man who lives in a hut on the roof. Half of the hut is a deep blue mural of the cover of The Great Gatsby, and the other half is a filthy pidgeon cage. He went into the cage cooing, picked one, and then took it out of my line of sight. I didn’t see that pidgeon again.

I’ve learned P is a chain-smoker, and took his first cigarette at 7am.

We went out on to have some breakfast, 葱蛋 (onion omelette), 菠菜 (spinach), some 香腸 (sausage) and some sort of porridge. The cost of living here is pretty low – I could spend just $5 a day on food if I needed to, except for electronics. P helped me get an unlimited data plan for 900元/month from 中華電信 (Chunghwa Telecom), yelling at the clerk in Taiwanese the entire while. Come to think of it, he’s been yelling at practically everyone in loud Taiwanese – cab drivers, waiters, shopkeepers, to, in his words, “show the people I am a local.” He’s basically an anti-rip-off shield.

Our Sri Lankan friend left today to go back to Taipei. Before he did, one of the cooks at breakfast asked me in Mandarin why our friend was “comparatively black”, to which I replied that he was an Austrian (whoops, my country names ain’t so great) with Indian parents. She accepted this terrible reasoning graciously.

P’s English is significantly better than my Mandarin, but he helps me all the same. I tried to tell him a story about one of the street dogs, so we stopped in the middle of a street yelling in slow Mandarin about how sad that was. But actually compared to India and Turkey, there are hardly any street dogs here. They’re probably all taken in by loving shopkeepers.

He hilariously hasn’t yet adopted American indirectness in his speech. He watched a YouTube video and asked me if it would be appropriate to tell a colleague that he “wanted to fuck the video girl.” Ai-ya.

第一章

I misjudged my arrival time into 臺北 (Taipei), and arrived at 10pm instead of 10am. Oops. The AirBnB host in 板橋 (Banqiao) was asleep by then so I figured I’d book a place using the airport’s WiFi. As luck would have it, in the lobby I met a transplanted Sri Lankan Aussie who had booked a hostel, and a native Taiwanese who had wanted to go to 高雄 (Kaohsiung). The high-speed rail had stopped running for the night, so my new friends and I split a cab to downtown (1015元) and stayed in a simple hostel.

That is, after we had a red-eye dinner. We split six dishes between the three of us including 金莎豆腐 (salted-egg fried Tofu), 苦瓜 (bitter melon), and a host of slaughtered animals I am too tired to remember.

Then we attempted to sleep, and the Taiwanese friend (whom I’ll call P) told us his parents had died and he sold their house in Kaohsiung, using the proceeds to open a tea shop in Sydney. P had come back home to study English in a hotel room by himself, because the business stressed him out. He hired a manager to take care of his tea shop while he was away.

P is lonely, an only child, and his extended family is mostly composed of what he calls 酒肉朋友 (fair-weather friends), so I’ve gone to Kaohsiung with him to teach him English while he teaches me Mandarin. I’ll be working on my Mandarin-language-learning software while I’m there.